Shaun Golden was in the back of his friend’s pickup truck, driving to a University of Georgia (UGA) tailgate 10 years ago—and he saw Julie walking down the street. “I literally jumped off the truck,” he says, making sure he could finally talk to her.

As a couple, he and Julie finish the story together, exclaiming, “We started talking, and it hasn’t stopped!”

Along with four other couples, the Goldens share moments from their relationships in “Love,” the first episode of the recent season of "Your Fantastic Mind." With relationships ranging from one month to decades old, their stories help demonstrate exactly what happens in your brain when you fall in love—and how that insight can help researchers at Emory find potential treatments for a variety of mental health disorders.

Can’t Help Falling in Love

“Falling in love is in many ways becoming addicted to another person,” says Helen Fisher, anthropologist and neuroscience researcher at the Kinsey Institute. “This is not an emotion—it’s a drive—it’s a basic mating drive that evolved millions of years ago to start the mating process.”

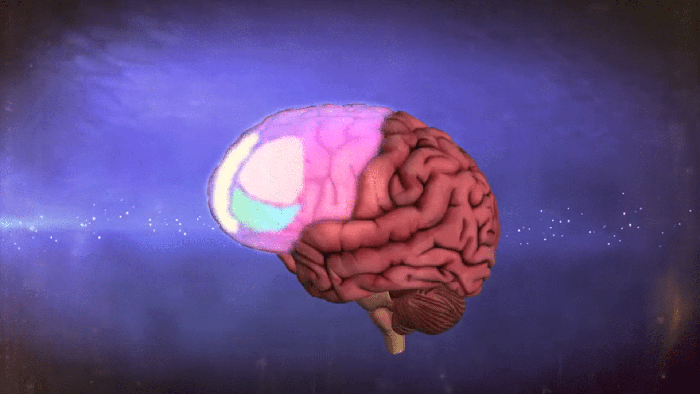

Fisher wanted to find out more about what happens to your brain when you’re in love. Using brain scanners, her team showed people photos of their partners and watched what parts of the brain activated. They all showed activity in what Fisher calls a “tiny little factory” called the ventral tegmental area, or VTA.

“That is a brain region that actually makes dopamine,” Fisher says, “and then sends dopamine to many brain regions, giving you that focus, the motivation, the craving—even the obsessive thinking—to win life’s greatest prize, which is a mating partner.”

Brant and Brian Rawls-Mcquillan describe the pull of attraction. “When you lose yourself to somebody else, there’s a certain amount of craziness that goes with it in the fact that you are no longer in control necessarily of all your emotions.”

Jill and John Rossino have been married 40 years and met as reporters in Little Rock, Arkansas. “I saw her on the air,” John says, recalling the way he felt for Jill, “and I said I really like that woman. She’s pretty sweet.”

Jerry Katz expresses a similar feeling when he encountered Martha Jo the first week she was at UGA. “I was attracted to her almost immediately, and that’s why I invited her back to the fraternity house.”

Researching Relationships

Neuroscientist and professor of psychiatry Larry Young, PhD, studies prairie voles—small hamster-sized rodents—at Emory University, and how their relationships are like ours. Like humans, voles have monogamous relationships and form family bonds.

“I’ve been studying these voles because I want to understand the biochemical and brain mechanisms that help us form social relationships,” Young explains.

“There’s something irresistible about their partner,” Young says. His team’s research found that voles that can form bonds have the receptors for the hormones oxytocin and vasopressin in the parts of the brain that are involved in reward and addiction.

“We think this pair bond is very similar to addiction; the animals are becoming addicted to their partner,” he says.

Young’s research also explores how some voles are less likely to form social relationships when they lose a parent early in life.

“From monogamy to shared parenting to nurturing, the answer to what makes these tiny creatures so similar to us is found in the brain,” Young remarks.